Author: Nicole Porter, N.A. PORTER & ASSOCIATES

For those of you who aren’t familiar with corrections, solitary confinement is defined as a form of imprisonment distinguished by segregation. It involves living in single cells with little or no meaningful contact to other inmates, strict measures to control contraband, and the use of additional security measures and equipment.

In my professional experience, I have always argued that conditions of confinement are far too severe to serve any kind of penological purpose. I have been involved in the criminal justice system and had contact both with inmates inside our nation’s prisons, and those in the community either on probation or parole. Some of those whom I’ve worked with or had contact with in my line of work have been those falsely accused and/or convicted of crimes they did not commit. Regardless of the offender’s circumstances, my research and experience has taught me first hand, what others in the field have concurred also; that solitary confinement should be strictly regulated as it tends to cause more harm than good.

There are several examples online illustrating solitary confinement’s harsh conditions, including filthy cells that are scarcely larger than a bed. When inmates are placed in solitary confinement this results in endless monotony and essentially a lack of human contact. This, for many prisoners, cause anxiety, depression, panic attacks, paranoia and in some cases, hallucinatory episodes. These are only among few of the atrocities people often suffer in solitary, but sadly, it is an unfortunate reality in many of our country’s institutions.

You may feel somewhat familiar with the experience of being locked up in solitary confinement as a result of it’s infamous appearances on the silver screen by actors like Tim Robbins in Shawshank Redemption. Actors portray lonely and idle inmates in a concrete box the size of a bathroom. Yet many people are unaware of the lasting harm it can wreak or of its widespread use.

Many experts and human rights advocates oppose the practice, citing a growing body of research that has revealed its pernicious impacts on mental health. One of those academics is Craig Haney, a social psychologist at the University of California, Santa Cruz. He is also the author of a 2018 article on the subject in the Annual Review of Criminology. In the article, Haney writes that not only are there serious psychological repercussions of solitary, but also that there’s an emerging consensus that the practice is costly and ineffective, in that it “does not achieve its intended objectives and may even worsen the problems it was designed to solve.”

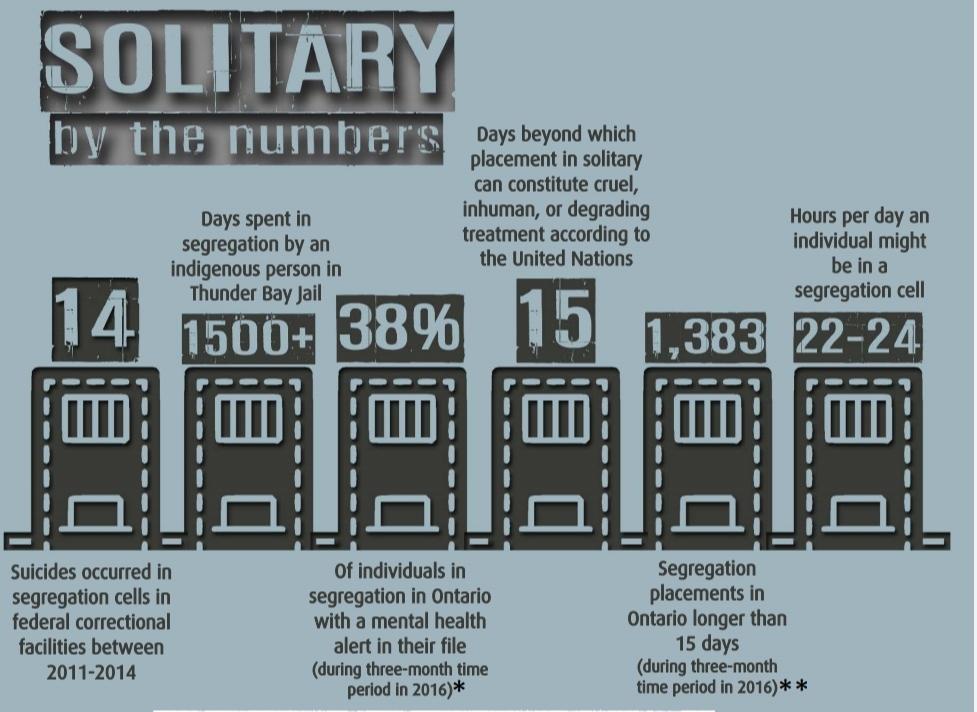

What I’ve personally found (and what others in the field have concurred), is that it’s not uncommon for a prisoner to spend up to 23 hours a day inside a solitary confinement unit. In these units, all activities occur: they eat, sleep and defecate all in the same 60 to 80 sq. feet of their cell. Sometimes the cells lack natural light; they may not even have a window in some cases. Many solitary confinement units have solid doors, so prisoners are literally encased in concrete and steel.

Prisoners, past and present, have told me that in solitary, they had nothing to pass the time. They weren’t given any education or vocational training. They often sat weeks or in some cases months, to access library services. Something as basic as reading, they were often denied. If they were lucky enough to get a magazine or book from a passing cart, they were set for weeks, their only way to pass time. But that would require them to be on a regular cell block; after all, passing carts didn’t randomly pass by solitary units. So inmates were basically sitting idle in their cells. There’s a monotony: They’re surrounded by the same voices, the same smells, the same light, the same four walls. They’re also deprived of human contact; many of these institutions deny prisoner contact visits. If they are lucky enough to get visitors approved, which is often a lengthy process to begin with, visits are closed contact and conducted through bulletproof glass.

When prisoners do get out of their cells, many are restricted to individual exercise areas that resemble cages where you would expect to see an animal in a zoo. Therefore, outside privileges are often seen as a joke. And in Canada’s toughest institutions, many prisoners feel unsafe even leaving the confines of their unit. Going outside is completely out of the question if you want to avoid an altercation or some form of assault. Inmates in these units are typically not engaged in any kind of group activity, instead remaining isolated. These are grim, dehumanizing and depriving environments.

Despite official government statements over the years that mandate using segregation only as a last resort, it is clear to many, that there is a troubling misuse of the practice in Canada as a whole. A quick Google search will show you incarceration statistics and you’ll see that many prisoners across the province are held in solitary confinement for months or years at a time.

Solitary confinement is often used as population management tool, in lieu of lack of resources at facilities and chronic overcrowding. Recent statistics suggest that administrative segregation may also be used outside of its legally permitted uses. According to the John Howard Society, administrative segregation is only to be used for incarcerated individuals who need protection, those who present as a risk to the safety of others, an individual who has been accused but not yet found guilty of serious misconduct within the facility, or those who request segregation.

Clearly, segregation is not being used as a last resort in all cases, or an exceptional practice by correctional authorities.

Ontario’s top courts found that long-term segregation was considered cruel and unusual punishment. For those of you who didn’t follow this or who weren’t involved in the criminal justice system like I happened to be, for five years the Trudeau government fought a legal battle to maintain the use of solitary confinement in federal prisons. Yes, you read that right… To uphold previous mandates regarding confinement. So essentially, that would mean zero changes. However, earlier this year after the long five year battle, it stopped fighting. Trudeau’s officials said the government would drop a Supreme Court appeal of two lower-court rulings, effectively making it illegal to hold a person in solitary for more than 15 consecutive days.

Ottawa’s decision is considered a good day for justice, despite unnecessary delays. And although I’m happy about the decision, I think it outlines further outdated and misused correctional practices.

The decision comes too late for many. Of the most infamous cases in the country; Ashley Smith, a teenager who took her own life in 2007 after spending a total of more than 1,000 days in solitary, and Edward Snowshoe, an Indigenous man who took his life in 2010 after 162 consecutive days in solitary. A young Indigenous man named Adam Capay was another case right here in Ontario; he spent a mind-blowing 1,647 days in isolation in prison, most of them in a cell that was perpetually lit. He had never been convicted of a crime, but was instead awaiting trial on a murder charge.

As a result of new mandates, these types of grotesque abuses are unlikely to ever be repeated in Canada, in either federal or provincial prisons. These changes come, in part, due to coordinated United Nations efforts to end solitary confinement exceeding 15 days or more. Anything exceeding this amount is legally considered a form of torture, and more specifically in Canada, this constitutes cruel and unusual punishment under our Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

But, here’s the catch: under Bill C-83, the CSC can still segregate violent or mentally ill prisoners who “are a threat to themselves or others, or whose lives are in danger” , and they can still be held in segregation for an indefinite period. So, instead going into what the CSC used to call “administrative segregation,” they will be sent to the same parking-space sized cells in what is now called “structured intervention units,” or SIU. In these units, inmates will be given a minimum of four hours a day outside their cell, with at least two of those hours dedicated to “meaningful human contact”. Under the legislation, this should include social programs or mental-health care that could help them return to the general population. However, from my professional experience working with offenders in and outside our federal Canadian prisons, access to these resources is increasingly difficult, and wait times for even basic literacy or medical intervention, is unreasonable and involve particularly long wait-times. Several inmates in a recent study of institutional issues, outlined to me wait times of three to six months to access library resources, two to three months for medical concerns, and sometimes up to six months to see a Correctional Investigator, if requested. When I asked inmates if they had ever requested a Correctional Investigator to review abuses on the inside, most of them laughed. When I probed deeper, I learned to request a formal investigator essentially put a target on your back. If other inmates learned about it, you would be subject to abuse, physical or otherwise, as it was essentially the same as being a ‘narc’.

So based on our legislation, this should eliminate the kind of abuse documented by the United Nations; the types of abuses such as 22 hours or more in a cell without meaningful human contact. This type of injustice shouldn’t occur, then right?

Except that it still could. The new law also carries stipulations; legal loopholes so-to-speak, mandating case reviews of inmates held in an SIU ONLY if the inmate does not get his or her minimum hours out of a cell, or minimum hours of meaningful human contact, for five straight days, or for 15 days out of 30.

Put another way for you, this means realistically, an inmate could remain locked in a cell for 14 non-consecutive days a month, with no meaningful human contact, for months on end.

There is no question that prisons must have some way to isolate inmates who are at risk, or a danger to others. There are situations that warrant this type of segregation. Also, there are institutional lockdowns that can make it impossible for inmates to leave their cell for several days at a time.

Some of you may be aware of recent efforts; advocates for women in prison recently headed to the Nova Scotia Supreme Court in Truro, N.S., aiming to end a practice they say “amounts to torture” in federal prisons.

After carefully reviewing systemic procedure in these institutions, I found out the use of “dry cells” involves keeping prisoners in a cell with round-the-clock lighting and without a flushing toilet or running water. Inmates are monitored through a glass window by guards, and security cameras are on 24 hours a day, even while prisoners are using the washroom. From what I understand, the cells are strictly meant to be used for male and female inmates suspected of ingesting or hiding contraband inside their bodies. Prisoners are watched until the item is removed through the person’s bodily waste.

Prisoners have been interviewed in an effort to determine if these practices are humane. Many women understood, having addiction issues themselves, that practices need to be in place to prevent drugs entering or being distributed in, these facilities. However, I believe, (as do many others) there has to be a way that’s less invasive, that’s more trauma-focused and that takes into account the value of the individual as well as the security of the institution.

The non-profit organization The Elizabeth Fry Society, which advocates for women in the criminal justice system, said the use of dry cells is unconstitutional “because it violates a person’s life, liberty and security of the person, under Section 7 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms”. The organization continues to fight for women’s rights and bring attention to the inhumane elements of dry cells.

Currently, there is no limit set out in the law or in correctional regulations stating how long a prisoner can be kept in dry cells, although in 2012, the former Correctional Investigator recommended an “absolute prohibition” on putting people in dry cells beyond 72 hours. The CSC added some oversight measures but declined to place a time limit on dry celling.

In June of this year, I was informed the current Correctional Investigator re-issued the recommendation and the CSC again declined to place a limit on the measure.

It appears efforts are being made to draw much needed attention to these matters. However, the fault often falls on our federal government and/or the CSC itself. Both entities need to be held accountable for their role in allowing these institutional atrocities to occur, because let’s face it, issues remain on the table and our CSC still refuses to place limits on these measures.

In conclusion, this means institutional abuses that are often considered cruel and unusual punishment, despite certain legislative changes, are still rampant in our prisons. Much needed changes will require the overall coordination and collective efforts of our government, the CSC, Correctional staff, investigators, and non-profit organizations like The Elizabeth Fry Society, to name only a few. These issues cannot be ignored and instead, must be addressed promptly to ensure these practices do not continue.

© Nicole Porter, N.A. PORTER & ASSOCIATES

Resources:

Jackson: Solitary Confinement in Canada

johnhoward.on.ca

globalnews.ca

ccla.org

www.efryottawa.com/