Author: N. Porter, N.A. PORTER & ASSOCIATES

Prisons are part of a larger system called punitive (or retributive) justice. Under this system, if someone breaks the law, they’re essentially punished for that wrongdoing. The punishment is supposed to be proportionate to the crime and should accomplish two things: rehabilitate the original law-breaker and stop others (or that person in the future) from committing the same crime. On paper, that looks pretty simple, and it looks fair. But in reality, it isn’t so straightforward.

In Canada, the criminal process is punitive by seeking to impose a punishment (deprivation or restriction) on the offender. The restorative process, on the other hand, seeks to compensate the victim, repair the harm, and facilitate the offender’s remorse.

Some characteristics of punitive justice include:

-the belief that punishment alters a person’s actions

-that the criminal will only take responsibility through punishment

-the belief that the infliction of pain will deter future criminal behavior

-a belief that action should be met with similar action

Punitive justice seeks to remove people from society and incarcerate them in penal institutions. When the system seeks to punish rather than rehabilitate, many of those who are incarcerated will repeat their actions upon release and become caught in the cycle of incarceration, when they are returned to penal institutions eventually.

Here are a few examples. Examples that truly make us question, whether punitive justice is the answer:

Let’s look at Simon. He is waiting for a bus when he sees the perfect opportunity to snatch a woman’s purse, and wallet. He’s down and out on his luck and in desperate need of cash. Without giving it another thought Simon takes the purse, contents inside, and starts running. A short time later, he is arrested and charged with assault and theft. A judge sentences Simon to three years in jail.

Sarah just turned 19 years old. She is currently caught up with a rough crowd. Her friends are involved in dealing illegal drugs. She is in the car when one of the people she is with opens fire and shoots another drug dealer. Sarah panics, and does what she is told: help load the body in the car. Together they drive the body to a dump site. A few days later Sarah and her friends are arrested. Although she has never been in trouble before and does not have a criminal record, Sarah now faces a possible 15 to 20 year sentence as an accessory to murder.

Does punitive justice really make sense in these cases?

First and foremost, any successful criminal justice system should promote public safety and respect for the law. In addition, criminal justice systems should deal with crime in a just, fair, efficient, and compassionate manner. While Canada’s criminal justice system works well in some areas, it isn’t meeting its intended objectives for most people who come in contact with it. For example, most people who become involved with our criminal justice system are vulnerable or marginalized individuals. They are struggling with mental health and addiction issues, poverty, homelessness, and prior victimization. It is not surprising then, that our criminal justice system is not equipped to address the issues that cause criminal behaviour in these groups, nor should it be. We are already dealing with an overburdened system; overcrowded by offenses that could be handled in a more appropriate and efficient manner, such as community justice programs. Personally, I think these issues are worsened by an over-reliance on incarceration.

Canada’s criminal justice system is facing many complex issues that affect its ability to deliver just, fair, compassionate results efficiently. According to the most recent review by Justice Canada, some simple short-term fixes were potentially identified but it was also noted that the system needed major reforms. The solutions they offered included minor Criminal Code amendments, programming enhancements, and calls for a fundamental and philosophical shift in the system’s principles and delivery of justice.

With a drastic over representation of minorities in prison, Canada’s criminal justice system is too quick, in my opinion, to criminalize the symptoms of vulnerable and marginalized people. This appears to be especially true for people with addictions and mental health issues. Unfortunately, in my experience, the system lacks in understanding and compassion for offenders and victims of crime. In addition, the justice system isn’t well integrated with the other social support systems, as it currently stands.

Many have called for an approach that tries to solve problems instead of looking only at facts and guilt. In addition to the system being overburdened with vulnerable and marginalized people, it is also burdened with a large number of lower level offences that are not a public safety concern.

Sure, the system does a good job of determining guilt in many cases, but its efficiency is undermined by sheer volume.

At the top of the list of recommendations to overhaul the punitive model, is to eliminate, or greatly restrict solitary confinement. This means, prohibiting the use of solitary confinement, especially for those with mental health problems. It also means regulating the use of solitary confinement to no more than 15 days.

In addition, it is suggested to improve court based solutions, rehabilitation and continuing care for offenders post-release. If there is, in fact, a TRUE focus on restorative justice instead of our punitive model, we should be offering enough structured and supervised programming to keep former inmates safely in communities. Most offenders on probation cannot follow conditions without help (they may have medical problems that affect their memory or ability to make decisions for example).

Federal, provincial, territorial, and municipal governments, as well as non-governmental and Indigenous organizations should work as a team to create a coordinated framework focused on individuals. This would allow courts to direct people to appropriate services. The more community support services, the greater the benefit.

Our system should focus less on guilt or innocence. It should focus less on sheer volume of guilty verdicts, and instead more on helping to rehabilitate and reintegrate people, especially those with mental illness and addiction. While prosecutors and judges don’t want to criminalize the mentally ill, criminal justice policy over the past decade has focused on increased use of prison sentences and has reduced the courts’ discretion in sentencing.

Since there is a large over-representation of Indigenous people in courts and jails, there have been suggestions for specialized courts or a justice system that takes the social, economic, and cultural factors at the root of criminal behaviour into account. In other words, we should be seeing a transition from the traditional “fact-finding” approach to one centred on healing.

A punitive model tends only, to focus on punishment, restriction and deprivation. Such a model is not effective. There should, however, be an increase in the use of restorative justice practices across the country.

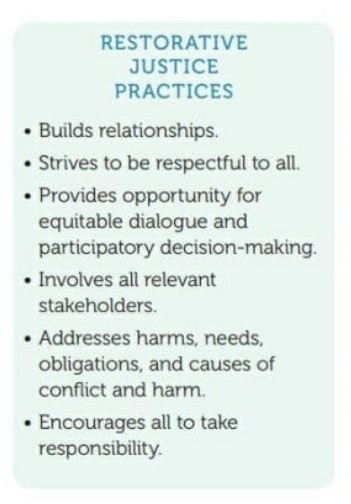

Restorative justice focuses on repairing the harm caused by crime while holding offenders responsible for their actions. It gives the parties directly affected by a crime the chance to identify and address their needs in the aftermath of a crime. It helps the victim (or victims), the offender and the community find a resolution that promotes restoration, reparation and reintegration and prevents future harm.

The restorative justice programs we have currently, are only available at various stages of the criminal justice process, and only for designated offences. The criteria and availability differ widely depending on the program and the jurisdiction. Many have called on the Minister of Justice to increase the use of this approach in Canada. There should be a philosophical shift in the way criminal justice is addressed in this country – one built on the foundation of accountability, responsibility, respect for all parties, as well as trauma and culturally-informed.

Across the country, restorative justice is often only available for certain lower level and non-violent offences. This is often viewed as a missed opportunity, given that restorative justice is said to work best for interpersonal violence and relationship breakdown. It makes sense then, that one of the top challenges identified, was a lack of restorative justice programs in Canada.

Since public safety remains the paramount concern of the criminal justice system, programs should attempt to reduce recidivism. If a program were to actually increase the chances of further criminal behaviour, most would agree that this would not be a success. Also, the needs of victims need to be adequately addressed. This is easily measured through controlled experiments testing the satisfaction levels of victims in the traditional system compared to a restorative approach. Lastly, the effects of a program on the community should be considered. For example, does the program reduce fear of crime and increase the perception of safety within a neighbourhood?

According to Sherman & Strang (2007), restorative justice compares well with traditional justice. Of consideration, is:

-It substantially reduces repeat offending for some offenders, although not all

-It reduces repeat offending more than prison for adults and at least as well as prison for youths

-It doubles (or more) the offences brought to justice as diversions from criminal justice

-When used as a diversion it helps reduce the costs of criminal justice

-It provides both victims and offenders with more satisfaction that justice had been done than did traditional criminal justice

-It reduces crime victims’ post-traumatic stress symptoms and the related costs, and

-It reduces crime victims’ desire for violent revenge against their offenders.

Restorative Justice sees crime as a breakdown of society and human relationships and attempts to mend these relationships through dialogue, community support, involvement, and inclusion. While denouncing criminal behavior, restorative justice emphasizes the need to treat prisoners with respect and allow them to reintegrate into the larger community. At the center of the restorative justice philosophy is the understanding of the importance of engaging victims and prisoners in a healthy way so they feel empowered and are supported to make meaning out of their experience. Restorative justice attempts to draw on the strengths of both prisoners and victims, rather than dwelling on their deficits.

Some provinces have had success implementing restorative justice approaches. One elderly man on parole, participated in a restorative justice program called Circle of Support and Accountability (CoSA) through the Micah Mission, a faith-based volunteer network in Saskatoon. Volunteers help high-risk offenders struggling to adjust to the outside world reintegrate into society. It’s not uncommon for individuals who, once released back into the community, to feel fearful, unadjusted, and unprepared. According to the Centre of Justice and Reconciliation – a Program of Prison Fellowship International, Cachene, who was released on parole, hasn’t been in trouble with the law for three years, not since his prison release. Much of his success is attributed to the restorative justice programs available for Cachene.

We need to view our justice system through a different lens. Prisoners in some cases, have no idea what restorative justice even means, let alone have access to relevant programming. Instead of inmates thinking about how to ‘stay out of trouble’ or ‘how to get out of prison’, why can’t we get them to think about what they’ve done? By participating in programming and by listening to these victims, inmates can hopefully stop and think (even in their cells, on their own time to reflect), about what they’ve actually done, and about how that affected people. Real people.

Another example is the Sycamore Tree project. Victims share their stories and in the process, both they and the prisoners are given techniques – through homework exercises, roleplays, empathy training, prayers and reflection strategies – to help heal their lives. Victims will speak of the trauma caused by the incident, the flashbacks, the financial and familial impacts.

Many restorative justice programs are based in indigenous cultures. Peacemaking circles are one of them. In the 1980s, circles were adapted for the criminal justice system thanks to the work of Yukon people and justice officials. Their goal was to bring the community and formal justice system closer together. In 1991, a judge in the Yukon Territorial Court introduced a sentencing circle. Circles are similar to victim-offender mediation in that they involve discussion. Circles can include whole families or just a few individuals.Circles are most commonly found in the Yukon, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan. Navajo peacemaking courts in the US have also used circles. They’re used for a variety of offenses for both juveniles and adults.

Amongst the potential benefits of restorative justice cited for victims, are the opportunities it can provide to the victim to: communicate with the offender who harmed them, should they wish to do so; speak to their lived experience; express the impact the crime has had; ask for answers to questions that matter to them and/or a sincere apology; and hold the offender accountable.

Of particular concern, is the lack of public understanding or awareness of restorative justice. For example, there is often a perception among the public that it is a “soft-on-crime” approach. But, in fact, the philosophy is actually based on personal accountability and responsibility.

That being said, not everyone who goes to prison is there because of racism. Not every person has been disproportionately sentenced. There are dangerous individuals in our federal prisons; serial killers and rapists behind bars. People who, from a public safety standpoint, and due to the nature and severity of their crimes, should be kept away from society, at all costs.

Further, most restorative justice programs are not equipped to deal with serious cases involving power inequalities, such as sexual assault or abuse, or domestic violence. Some programs have devoted extensive effort to training, consultation and partnership with appropriate supporting agencies to offer this form of justice in some of these cases, but that is not the norm. A number of countries are, however, exploring options for developing guides or standards to assist practitioners in assessing risk and applying restorative justice in cases of interpersonal violence and sexual assault.

However, restorative justice programs can be effective in the other percentage of cases. For the first timers, for the people who made a mistake, for the person who turned to gangs because they didn’t have a choice, for the person who stole to put food on their table… Focusing on why someone does something – why they feel like they had to do something – makes it easier to come from a place of empathy rather than punishment. For example, care-centered policies focus both on the individual and on larger communities. It tells us to focus on the whole story. For example: If someone steals from a grocery store because they’re living in poverty and have to feed their family, why should they be punished in the same manner? Why shouldn’t we look at how things can systemically change so that no one has to steal food? The system we have doesn’t work, but not because it’s “broken”; it was just never made for true healing, compassion, or justice.

When it comes to our current justice system, that problem really boils down to oppression, violence, and a lack of healing. No alternatives to the punitive justice system will work if we’re not looking at the world through a transformative justice lens.

Resources:

www.ncjrs.gov

www.victimsweek.gc.ca

Restorativejustice.org